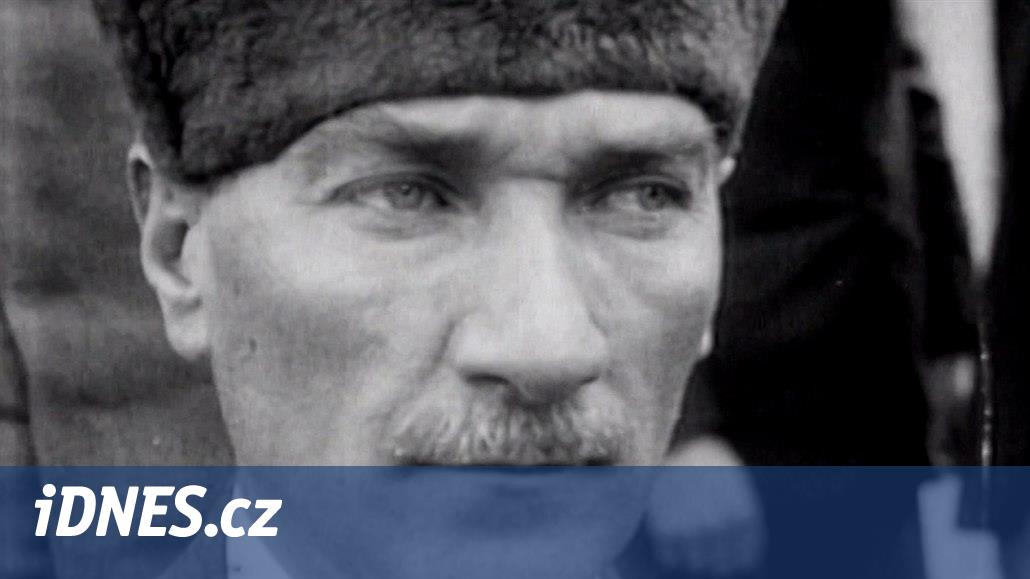

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder and first president of the Republic of Turkey, instituted radical reforms that rapidly transformed Turkey from an Islamic Ottoman state into a modern, secular nation-state. Atatürk’s secular reforms fundamentally changed the country by separating religion from government, replacing Islamic law with secular European codes, and eliminating the political power held by religious leaders and institutions.

Abolishing the Caliphate

One of Atatürk’s most significant early reforms was abolishing the Ottoman Caliphate in 1924. As Caliph, the Ottoman Sultan had been the supreme religious and political leader of Sunni Muslims worldwide Ending this centuries-old institution separated the Turkish state from Islam and eliminated the politico-religious authority held by the Sultan/Caliph This reform sent a clear message that religion would no longer play a role in governing Turkey.

Removing Islam as the State Religion

The new Turkish constitution of 1924 established Turkey as a secular state. Islam was removed as the official state religion, and constitutional recognition of Islam was repealed. This profound change officially separated mosque from state by removing religion as a basis for government.

Banning Religious Orders and Titles

Atatürk banned religious orders, prohibiting their meetings and rituals. He closed Sufi lodges and dervish meeting houses, eliminating the political influence these brotherhoods had held. The office and title of Sheikh al-Islam, the powerful religious leader who oversaw religious law and advised the Sultan, was abolished. Banning these religious institutions and leadership roles curtailed Islam’s sway over political affairs.

Replacing Sharia Law with Secular Codes

One of Atatürk’s most far-reaching reforms was replacing Islamic Sharia law with secular European legal codes in the 1920s and 30s. The new Civil Code was based on Switzerland’s and the Penal Code on Italy’s. Adopting secular law removed religion as the foundation for Turkey’s legal system, restricting Islam’s control over social and political life.

Limiting the Influence of Religion in Public Life

Atatürk instituted reforms aimed at reducing Islam’s visibility and influence in public life. The fez hat and the veil were discouraged as symbols of religious tradition. The Muslim calendar was replaced with the Gregorian calendar. The weekly holiday was moved from Friday to Sunday. These changes diminished the public role of Islam and oriented Turkey toward secular Western norms.

Promoting Secular Education

Atatürk closed Islamic madrasas, replacing them with secular state schools. Religious education was banned in favor of secular curricula. Co-education of boys and girls became mandatory. These educational reforms sought to remove religion’s influence over the younger generation by making secular education the norm.

Atatürk’s sweeping reforms secularized all major Turkish institutions, from government administration to legal codes to education. Removing Islam’s role in Turkish public life was the defining aim of Atatürk’s reforms, profoundly transforming a once theocratic Ottoman society into the secular Republic of Turkey. Although controversial, these reforms created a progressive, forward-looking country by forcibly modernizing an Islamic society along Western secular lines.

Recent NewsAug. 19, 2024, 11:07 AM ET (AP)

Secularism included the reform of law, involving the abolition of religious courts and schools (1924) and the adoption of a purely secular system of family law. The substitution of the Latin alphabet for the Arabic in writing Turkish was a significant step toward secularism and made learning easier; other measures included the adoption (1925) of the Gregorian calendar, which had been jointly used with the Muslim (Hijrī) calendar since 1917, the replacement of Friday by Sunday as the weekly holiday (1935), the adoption of surnames (1934), and, most striking of all, the abolition of the wearing of the fez (1925), a hat that reformers saw as a sign of cultural backwardness. The wearing of clerical garb outside places of worship was forbidden in 1934.

These changes, coupled with the abolition of the caliphate and the elimination of the dervish (Sufi) orders (see Sufism) after a Kurdish revolt in 1925, dealt a tremendous blow to Islam’s position in social life, completing the process begun in the Tanzimat reforms under the Ottomans. With secularism there came a steady improvement in the status of women, who were given the right to vote and to sit in parliament.

Vital as these changes were, in many cases they were primarily matters of appearance and style. Structural changes in society took longer. At the first census, in 1927, the population was put at 13.6 million, of which about one-fourth was urban. In 1940 the population was 17.8 million, but the urban proportion was almost unchanged. In 1938 the per capita income and literacy rate were both below comparable figures for developed countries.

Foreign policy was subordinated to internal change. The loss of Mosul was accepted (June 5, 1926). Hatay province along the Syrian border, however, was recovered. It was given internal autonomy by France in 1937, occupied by Turkish troops in 1938, and incorporated into Turkey in 1939. Turkey followed a neutralist policy, supported the League of Nations (which it joined in 1932), and sought alliances with other minor powers, leading to the Balkan Entente (1934) and the Saʿdābād Pact with Iran, Iraq, and Afghanistan (1937).

Turkey after Kemal “Atatürk”

The autocratic, dominating, and inspiring personality of Kemal Atatürk (“Father of Turks,” as Mustafa Kemal came to be known) had directed and shaped the Turkish republic. At his death in 1938 his closest associate, İsmet İnönü, was elected president. With the approach of World War II (1939–45), foreign affairs assumed greater importance. An alliance with the Allied powers Britain and France (October 19, 1939) was not implemented because of Germany’s early victories. After Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union (June 1941), there was popular support for an alliance with Germany, which seemed to offer prospects of realizing old Pan-Turkish aims. Although a nonaggression pact was signed with Germany (June 18, 1941), Turkey clung to neutrality until the defeat of the Axis powers became inevitable; it entered the war on the Allied side on February 23, 1945, mere weeks before the war’s end. The great expansion of Soviet power in the postwar years exposed Turkey in June 1945 to Soviet demands for control over the straits connecting the Black Sea with the Aegean and for the cession of territory in eastern Anatolia. It was also suggested that a large area of northeastern Anatolia be ceded to Soviet Georgia. This caused Turkey to seek and receive U.S. assistance; U.S. military aid began in 1947 (providing the basis for a large and continuing flow of military aid), and economic assistance began in 1948.

The war also brought changes in domestic policy. The army had been kept small throughout the Atatürk period, and defense expenditure had been reduced to about one-fourth of the budget. The army was rapidly expanded in 1939, and defense expenditures rose to more than half the budget for the duration of the war. Substantial deficits were incurred, imposing a severe economic strain, which was aggravated by shortages of raw materials. By 1945, agricultural output had fallen to 70 percent of the 1939 figure and per capita income to 75 percent. Inflation was high: official statistics show a rise of 354 percent between 1938 and 1945, but this figure probably understates the fall in the value of money, which in 1943 was less than one-fifth of its 1938 purchasing power. One means chosen by the government to raise money was a capital levy, introduced in 1942, arranged to fall with punitive force upon the non-Muslim communities and upon the Dönme (a Jewish sect that had adopted Islam). The war did provide some stimulus to industry, however, and enabled Turkey to build up substantial foreign credits, which were used to finance postwar economic development.

The most notable change in the postwar years was the liberalization of political life. The investment in education was beginning to show some return, and the literacy rate had risen to nearly one-third of the adult population by 1945. A growing class of professional and commercial men demanded more freedom. The Allied victory had made democracy more fashionable; accordingly, the government made concessions allowing new political parties, universal suffrage, and direct election.

From a split within the CHP, the Democrat Party (DP) was founded in 1946 and immediately gathered support. Despite government interference, the DP won 61 seats in the 1946 general election. Some elements in the CHP, led by Prime Minister Recep Peker (served 1946–47), wished to suppress the DP, but they were prevented from doing so by İnönü. In his declaration of July 12, 1947, İnönü stated that the logic of a multiparty system implied the possibility of a change of government. Prophetically, he renounced the title of “National Unchangeable Leader,” which had been conferred upon him in 1938. Peker resigned and was succeeded by the more liberal Prime Ministers Hasan Saka (1947–49) and Şemseddin Günaltay (1949–50).

Other restrictions on political freedom, including press censorship, were relaxed. The first mass-circulation independent newspapers were established during the period. The formation of trade unions was permitted in 1947, though unions were not given the right to strike until 1963. A far-reaching land-redistribution measure was passed in 1945, although little was done to implement it before 1950. Other political parties were established, including the conservative National Party (1948); socialist and communist activities, however, were severely repressed.

In the more open atmosphere, the DP was able to organize in the villages. The CHP, despite its local village institutes, had always been the government party and had little real grassroots organization. The Democrats were much more responsive to local interests. The DP won a massive victory in the 1950 elections, claiming 54 percent of the vote and 396 out of 487 seats. The CHP won 68 seats, the National Party 1. The DP victory has been attributed variously to American influence, social change, a desire for economic liberalization, better organization, religious hostility to the CHP, and a bad harvest in 1949. Perhaps the ultimate reason, however, is simply that in 27 years the CHP had made too many enemies.

How did Atatürk reform Turkey?

FAQ

How did Atatürk change Turkey?

What is the secular movement in Turkey?

What was the reform that helped transform Turkey in the 1920s?

Why did Atatürk abolish the caliphate as part of his reform movement?