Ticks are a huge nuisance for humans, pets, livestock, and wildlife. These tiny arachnids survive by feeding on the blood of mammals, birds, and reptiles. Tick bites can transmit nasty diseases like Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and anaplasmosis. With tick populations on the rise, many people wonder if turkeys can help control these pesky parasites. In this article, we’ll explore the tick-eating abilities of our feathered friends.

An Insatiable Appetite for Ticks

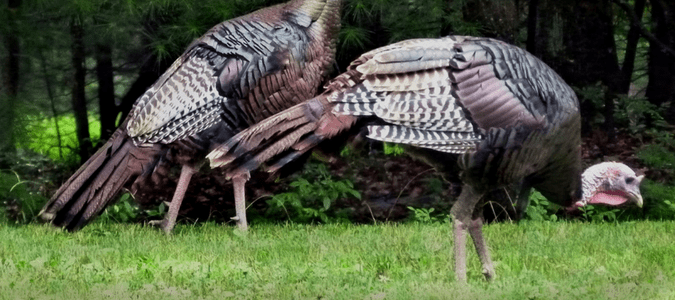

Turkeys possess several qualities that make them excellent tick predators. Their sharp eyesight helps them spot ticks easily, even when they are hidden in vegetation. Turkeys also spend a lot of time preening and grooming themselves, allowing them to find and consume ticks on their bodies.

But perhaps their most useful trait is their insatiable appetite for ticks. Turkeys are true tick-eating machines! An adult turkey may devour over 200 ticks per day under optimal conditions. To put that in perspective a mating pair of turkeys could potentially consume over 3800 ticks daily when they have a clutch of poults. That’s more ticks than most birds eat in an entire year!

Turkeys use their strong beaks and sharp claws to efficiently pluck ticks from their feathers and skin during grooming sessions They also eat ticks they find while foraging on the ground Ticks make up a small but consistent part of a turkey’s diverse diet.

Evaluating Their Impact on Tick Populations

Given their voracious tick-eating abilities, could turkeys make a dent in tick populations? Researchers have conducted several studies to evaluate their potential for tick control. The findings indicate turkeys do consume ticks in large numbers, but likely have a negligible impact on overall tick densities

There are a few reasons turkeys fall short as tick control agents:

-

Ticks are not a preferred food source – While turkeys eat lots of ticks opportunistically, ticks only make up a small fraction of their diverse diet. They don’t seek out ticks as a primary food source.

-

Tick reproduction outpaces consumption – A single tick can lay thousands of eggs in its lifetime. So even thousands of ticks consumed per turkey does little to suppress population growth.

-

Ticks have many host options – Ticks feed on birds, mammals, reptiles, and amphibians, so they aren’t dependent on turkeys as hosts for survival.

So while an individual turkey might eat impressive numbers of ticks, wild turkey populations do not significantly reduce tick densities across an ecosystem. Their tick-eating activities likely have a negligible impact on disease transmission rates.

Other Tick-Eating Birds

While turkeys reign supreme in terms of total ticks eaten, they aren’t the only feathered friends that feast on ticks. Birds with qualities similar to turkeys also consume ticks regularly:

-

Chickens: Sharp vision and ground foraging make chickens decent tick predators. Limited research indicates they are less efficient than turkeys though.

-

Guinea fowl: Valued by many as natural tick deterrents, guinea fowl eat ticks but likely have minimal benefit for population control.

-

Partridges: As ground foragers, partridges find and eat ticks often. But their smaller size limits total consumption.

-

Peafowl: Large, ground-dwelling peafowl will readily eat ticks encountered while foraging. But they do not seek them out as a food source.

-

Quail: Fast-moving quail find ticks while foraging but eat fewer than turkeys due to their small size.

-

Woodpeckers: Woodpeckers remove embedded ticks when grooming, but their arboreal nature limits ground tick consumption.

While these birds eat ticks frequently, none can match the turkey in terms of total ticks consumed per day. But collectively, they do make a minor dent in tick numbers.

The Importance of Tick Prevention and Control

While wild turkeys and other birds eat ticks in impressive numbers, don’t expect them to eliminate your tick problems completely. Their tick-eating activities likely have minimal impact on the growing public health threats posed by tick-borne diseases.

The most effective way to protect yourself from tick bites is through prevention and control measures:

- Use EPA-registered repellents when outdoors

- Wear light-colored clothing that covers the arms and legs

- Conduct frequent tick checks after outdoor activity

- Keep grass mowed and brush cleared in outdoor spaces

- Ask your vet about anti-tick medications for pets

- Consider professional tick control services for your property

So while we should appreciate the turkey’s noble battle against ticks, don’t forget to take precautions against these disease-carrying pests yourself. With smart prevention habits, we can enjoy the outdoors without worrying about nasty tick bites.

A Brief History Lesson

It is important to remember that the story of wild turkeys in Maine begins long before reintroduction, and that they are in fact a native species. As such, they fall squarely within MDIFW’s duty to preserve, protect, and enhance Maine’s wildlife resources.

Prior to settlement, wild turkeys existed in significant numbers, particularly in York and Cumberland Counties. But unrestricted hunting paired with a massive reduction of forest habitat as agricultural practices intensified led to the total loss of Maine’s population by the early 1800s. Attempts to bring wild turkeys back to our state began in the 1940s with pen raised wild turkeys that were unsuccessful. The first successes with reestablishment didn’t occur until the late 1970s, adopting the strategy of trapping full grown wild turkeys from other states and releasing them in Maine. It was a challenging recovery, and we are lucky to have the healthy population that exists today.

Lyme disease also has an extensive history here. A team of Yale researchers used genome sequencing to trace the origin and spread of tick-borne diseases. They discovered that the bacteria that causes Lyme disease is not a newcomer to the United States. It has been circulating in North America long before the reintroduction of turkeys. In fact, it has been around for over 60,000 years, well before humans were even in the picture. The current rise in Lyme disease was not caused by a reintroduction of the bacteria or a recent mutation of the bacteria.

Black-legged ticks (commonly known as deer ticks) are the primary vector for Lyme disease (and other tick-borne diseases) and were first documented in southern Maine in the 1980s. Their population has since increased, their range has expanded, and Lyme disease is on the rise. The timing of the expansion of ticks does coincide with the reestablishment of wild turkeys, and with such suspicious timing, turkeys seem like an easy scapegoat. But, as every good scientist knows, correlation does not imply causation.

In other words, two independent events trending similarly over time does not definitively prove that one produced the other. Why? There are countless other variables in play! Changes in temperature, humidity, human population, wildlife populations, habitat and much more were also occurring at the same time, so the determination of cause and effect is complex to say the least. A good place to begin is to understand the life cycle of the tick.

A parasite is dependent on its host for survival. Deer ticks feed on three separate hosts throughout their life cycle. Small mammals, such as mice, are typical hosts for the first stage and mid-sized mammals are the most common hosts for the second stage. White-tailed deer are the primary host for the final adult stage, providing both a source of nutrients and a method of dispersal. So where do turkeys fit in?

Black-legged tick life stages Photo by the U.S. CDC

A number of scientific studies have been conducted to investigate interactions between turkeys and ticks and determine if wild turkeys are likely beneficial hosts for deer ticks at any stage in the life cycle. The results were clear. Deer ticks rarely successfully feed on turkeys. While turkeys can and do sometimes carry ticks, it’s not at high levels, and most are quickly consumed during preening prior to becoming engorged, limiting spread. So, could turkey preening and foraging actually decrease tick densities? Unfortunately, no. Study results show that turkeys are relatively ineffective predators of ticks. Overall, wild turkeys carry a few ticks and eat a few ticks, and have a net zero impact.

In addition to hosts, ticks also require suitable habitat and favorable environmental conditions such as humidity and temperature. Milder seasons have contributed to the spread of deer ticks in Maine. Warmer temperatures support higher survival by giving ticks more time to find hosts and by allowing more ticks to lay eggs and more eggs to survive to hatch.

Scientists continue to research how variables such as changes in tick habitat, host habitat, host density, host health, and climate relate to each other and to the proliferation of ticks in our state.

“If we just have a better understanding of all the factors taken together, I think we could do a better job of helping people control deer ticks and prevent disease.” -Susan Elias, PhD

Have Turkeys Been Wrongly Accused for the Uptick?

The topic of turkeys is one which has no doubt sparked great debate around many Thanksgiving tables in Maine. Some are thankful for this prized gamebird’s comeback, while others are “ticked” off about their reintroduction. The best way to address this dispute is to look to science for the answers.

Numerous studies have shown that while turkeys will not solve our state’s tick problem, they also did not create it. The social, environmental, and economic impacts that wild turkeys have in Maine are overwhelmingly positive, solidifying them as an appropriate symbol of thankfulness as we enter the holiday season.

Ask Dr. Mike: Ticks & Wild Turkeys

FAQ

Do turkeys keep ticks away?

What animal eats the most ticks?

How many ticks does a turkey eat per day?

Do chickens and turkeys eat ticks?